WHY THE WAITANGI TRIBUNAL IS LYING TO MAORI

By Ian Wishart

There comes a time in any society dominated by ruling classes when someone from the peasantry has to stand up and ask the age-old question: “why is the Emperor wearing no clothes?”

That time, in New Zealand’s case, is now.

For the past 40 years, New Zealanders both Maori and Pakeha have been backseat spectators as the Treaty of Waitangi has gradually been re-written, re-interpreted and ultimately tortured to become something it never was, and two recent Waitangi Tribunal rulings show it’s time to blow the whistle before players get hurt.

Two weeks ago, the Tribunal issued a ruling, praised by some radio commentators, that claimed Maori had never given up sovereignty to the British Crown. Today, the Tribunal has issued a 618 page ruling attempting to enforce that new Maori ‘sovereignty’ by suggesting Parliament has no power to change laws relating to Maori and that such issues must be decided by Maori.

Both of these rulings are demonstrably wrong – not because I say so, but because Maori who ratified the Treaty of Waitangi back in the 1800s say so in their own words.

Both rulings hinge on the same premise: that Maori never ceded sovereignty to the Crown. Clearly that is the view that now dominates the Waitangi Tribunal’s thinking, so the question remains, is it right?

Some commentators argue that because the Waitangi Tribunal has the sole ‘power’ in New Zealand to interpret the Treaty, that means the claims must be right; the only body in New Zealand with authority to make a ruling has made its ruling, so live with it! The people who follow that logic are however, with respect, displaying intellect as shallow as a birdbath. Although parliament has the power to pass a law ordering the death of all blond, blue-eyed babies at birth, having the power to issue an edict does not by definition make the edict right or even sustainable in logic. Adolf Hitler issued lots of edicts that were lawful in their time, even if factually wrong.

And so it is with the Waitangi Tribunal. It might have the power to push the government around but it does not have the power to push the people of New Zealand around. If what the Waitangi tribunal is saying is false, the Tribunal should be disbanded pending an inquiry into philosophical and scholarly corruption of the unit in my view.

I can prove the Waitangi Tribunal is wrong when it says Maori never gave up sovereignty over New Zealand. In fact, not only ‘can’ I prove it, I already have.

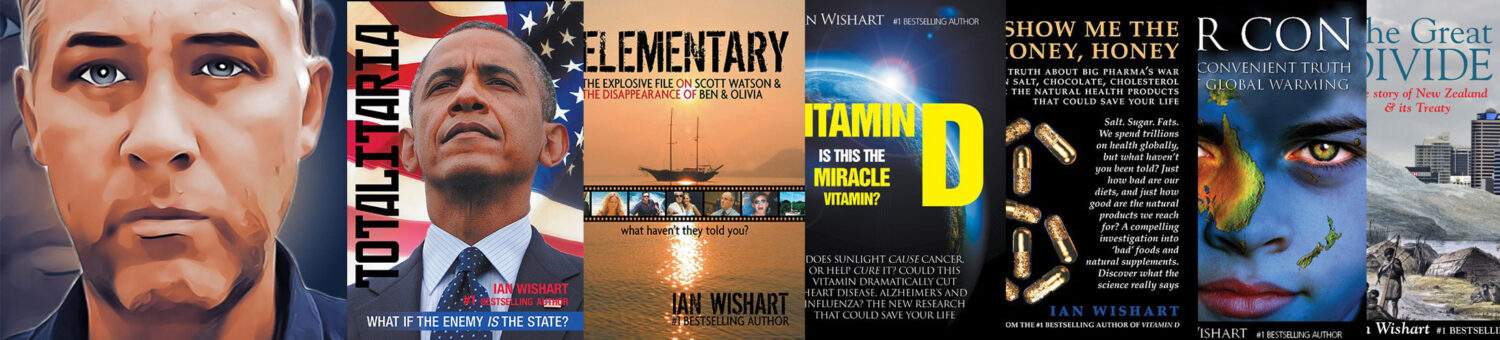

Exhibit A, the smoking gun, is my book The Great Divide.

“You are aware there are no laws in New Zealand; there is no king. They feel the want of this, and they cannot make a king from their own chiefs, as every chief would think himself degraded if he should be put under the authority of a chief of their own.”[i]

Those are the words of missionary Samuel Marsden in 1837, explaining why Maori wanted an outside sovereign to rule the country. His key take home point…there could be no Maori sovereignty because each tribe considered itself supreme – a position that kept causing tribal wars and bloodshed. They wanted the Brits to take over and establish peace under a sovereign everyone could respect.

An argument raged between two factions in Britain. One faction saw Maori society as a basket-case, as indeed Maori saw it themselves, needing a sovereign to step in and bring Western enlightenment. The other faction saw Maori society as a museum piece in need of isolating and protecting so that Maori could continue living without contact with the civilised world. This faction came to dominate in Australian settlement, treating the native Aboriginals as a race to be sidelined in the outback rather than welcomed into cities. The logic was that primitive cultures should be allowed to maintain their culture unmolested by modernity.

As explained, while some Maori agreed with the latter sentiment, wanting to turn back the clock and send the whites home, most Maori fell into the first camp, wanting all the benefits of Western civilisation under British rule so that decades (in fact hundreds of years) of bitter tribal wars could be ended.

Queen Victoria, through her officials, told Captain William Hobson that the best interests of the Maori people would probably be served by surrendering sovereignty in return for British protection:

“Believing, however, that their own welfare would, under the circumstances I have mentioned, be best promoted by the surrender to Her Majesty of a right now so precarious, and little more than nominal, and persuaded that the benefits of British protection and of laws administered by British Judges would far more than compensate for the sacrifice by the natives of a national independence which they are no longer able to maintain, Her Majesty’s Government have resolved to authorise you to treat with the aborigines of New Zealand for the recognition of Her Majesty’s sovereign authority over the whole or any part of those islands which they may be willing to place under Her Majesty’s dominion.” [quoted in The Great Divide, page 149]

The Waitangi Tribunal would have the public believe that ancient Maori society was civilised and they all lived in Smurf-like village settlements, at one with nature. This is far from the truth, a typical Maori village in the early 1800s committed more beheadings than ISIS and al Qa’ida ever have in modern times:

“Not less than 40 canoes came into the harbour from a war expedition, with prisoners of war, and the heads of a number of chiefs whom they had slain in battle. I went onshore and saw the prisoners and the heads when they landed. The sight was distressing beyond conception,” wrote Samuel Marsden at one point. [Great Divide, page 118].

Another missionary, Samuel Leigh, stumbled across the beheading of a child:

“One day, as I was walking on the beach, conversing with a chief, my attention was arrested by a great number of people coming from a neighbouring hill. I inquired the cause of the concourse, and was told that they had killed a lad, were roasting him, and going to eat him. I immediately proceeded to the place, in order to ascertain the truth of this appalling relation. Being arrived at the village where the people were collected, I asked to see the boy.

“The natives appeared much agitated at my presence, and particularly at my request, as if conscious of their guilt; and it was only after a very urgent solicitation that they directed me towards a large fire at some distance, where, they said, I should find him. As I was going to this place, I passed by the bloody spot on which the head of this unhappy victim had been cut off; and, on approaching the fire, I was not a little startled at the sudden appearance of a savage-looking man, of gigantic stature, entirely naked, and armed with a large axe. I was a good deal intimidated, but mustered up as much courage as I could, and demanded to see the lad. The cook (for such was the occupation of this terrific monster) then held up the boy by his feet. He appeared to be about fourteen years of age, and was half roasted.

“I returned to the village, where I found a great number of natives seated in a circle, with a quantity of coomery (a sort of sweet potatoe) before them, waiting for the roasted body of the youth. In this company were shown to me the mother of the child. The mother and child were both slaves, having been taken in war. However, she would have been compelled to share in the horrid feast, had I not prevailed on them to give up the body to be interred, and thus prevented them from gratifying their unnatural appetite.” – [cited at page 115 of The Great Divide]

In one battle in Auckland, thousands of Maori were killed and eaten where Glen Innes and Mt Wellington now stand.

Lest critics accuse me of being racially insensitive, I married a part-Maori woman, my children can trace their whakapapa. This is not being written to inflame, but to inject some reality about the life that Maori tribes were desperate to leave behind by signing the Treaty.

So how do I prove that Maori knew they were ceding sovereignty?

Like it or not, the perception being sold to Maori and Pakeha on a daily basis is that the tribes always kept their own supreme sovereignty, never relinquished it, and deserve to be treated as equals to the New Zealand government for the purposes of setting the laws of this country. This all hangs on the word “kawanatanga” allegedly not meaning sovereignty.

If, as Michael King wrote, Maori at Waitangi truly did not equate kawanatanga with sovereignty, then what are we to make of the comments of Ngapuhi’s Rewa at Waitangi in 1840, quoted here directly from King’s own book:

“What do we want of a governor? We are not whites nor foreigners. We are the governor – we the chiefs of this land of our ancestors!”202

You couldn’t get a clearer example that Maori knew kawanatanga was interchangeable with sovereignty: “We are the sovereign – we the chiefs of this land of our ancestors”.

King – perhaps because it would have shot his thesis down – did not quote the end of Rewa’s speech, where he stated:

“Do not sign the paper. If you do you will be reduced to the condition of slaves, and be compelled to break stones on the roads. Your land will be taken from you and your dignity as chief will be destroyed.”

It is hard to believe that academics and authors have been able to draw taxpayer funded salaries and study grants to argue that Maori had no awareness they were transferring sovereignty at Waitangi.

Remember Te Kemara’s speech?:

“Were we to be an equality, then perhaps Te Kemara would say yes. But for the Governor to be up and Te Kemara to be down – Governor high, up, up, up, and Te Kemara down low, small, a worm, a crawler. No, no, no.”

Another Ngapuhi leader, Kawiti, told those gathered at Waitangi:

“We Native men do not wish thee to stay. We do not want to be tied up and trodden down. We are free. Let the missionaries remain, but, as for thee, return to thine own country…I, even I, Kawiti, must not paddle this way or paddle that way because the Governor said ‘No’, because of the Governor, his soldiers and his guns.”

How can anyone reconcile these paragraphs with the claim that Maori did not know the Treaty involved a transfer of sovereignty and control?

But a legalistic word-by-word approach to decoding the Treaty is not necessarily the last word, so to speak. There is another way to find out what Maori understood.

When courts have difficulty understanding the context (and therefore precise meaning) of an Act of Parliament, they sometimes go back to the parliamentary debates that accompanied the passing of the law in question, to get a feel for what legislators actually intended. In the same manner, concentrating on the precise wording of the Treaty of Waitangi only gets you so far.

To get a proper handle on it, we jump forward now 20 years, to a gathering of ariki – paramount chiefs – and rangatira, at Kohimarama in Auckland in July 1860. The purpose of this “runanga” – or tribal council – was to discuss how Maori had fared in the 20 years since Waitangi had been signed, and seek their views on current issues affecting them.

The proceedings, and thus the speech transcripts below, were published in Te Karere, the main Maori newspaper, that month.

To those who argue that Maori never intended to sign away sovereignty over New Zealand to the Crown, and never understood that to be the case, we produce chief Wikiriwhi Matehenoa of Ngati Porou on the East Cape, who told the up to 200 chiefs gathered (a much higher number than those who had gathered at Waitangi): “We are all under the sovereignty of the Queen, but there are also other authorities over us sanctioned by God and the Queen, namely, our Ministers.”

The Maori translation is illustrative of what he understood. He used the words “te maru o te Kuini”, where the word ‘maru’ means literally “power, authority” translated in 1860 at the conference as sovereignty.[ii]

Wikiriwhi further backs that up in his phrase “sanctioned by God and the Queen”, rendered in Maori, “mana whakahaere o te Atua raua ko te Kuini”. The word “raua” in this sense means “combined” and refers back to the “mana” of both God and Queen”.

To flip Michael King’s analysis back on itself, the chief did not use the phrase “te kawanatanga o te Kuini”, if governorship was all they actually understood the Queen’s sovereignty to be.

It is abundantly clear that Ngati Porou fully understood Queen Victoria’s sovereignty over New Zealand. Te maru; the power, the authority.

The Ngati Raukawa chief Horomona Toremi, of Otaki, went so far as to explain that – post Waitangi – “You over there (the Pakehas) are the only Chiefs. The Pakeha took me out of the mire: the Pakeha washed me. This is my word. Let there be one Law for all this Island.”[iii]

Then there’s Te Ahukaramu’s position: “First, God: secondly, the Queen: thirdly, the Governor. Let there be one Queen for us. Make known to us all the laws, that we may all dwell under one law.”[iv]

The concept that the Queen set the law for all New Zealanders, Maori and Pakeha alike, was clearly understood, as was the Queen’s position under God, and the Governor’s ranking underneath the Queen. Beneath the top three, Maori and Pakeha citizens. “Kia kotahi te Kuini mo tatou” – one Queen over all of us.

Te Ahukaramu was even more explicit about the evolution of the Maori king movement, describing it as a usurpation of the Queen’s sovereignty, and noting that the recently deceased first Maori king had recognised the authority of “the Queen, and the Government.

“If any of the tribes should set up a Maori King, then let them be separated from the Queen’s ‘mana’.” In Maori, it reads, “me wehe ratou i runga i te mana o te Kuini”.

A few paragraphs back we looked at why Maori had invited the British monarch to become sovereign over New Zealand, because they needed to unite behind someone with higher mana than any individual New Zealand chief.

As chief Wiremu Patene told the Kohimarama gathering, even the Maori King’s mana was next to nothing against Victoria’s:

“But remember, Governor, that (the Maori King) is child’s play. The Queen’s mana is with us. Let me repeat it, that work is child’s play.”

With the huge inroads that Christianity made in the 1830s, it’s actually important to realise in this discussion that most of the Maori chiefs at Waitangi probably had a better and deeper understanding of the Bible than many people today. For Maori, the concept of submission to a higher authority was something many of them had now personally done, and that was part of the understanding they brought to Waitangi; they knew they were submitting.

“Let me make use of an illustration from the Scriptures,” chief Hamuera of Ngaiterangi told the runanga. “Jesus Christ said he was above Satan. So the Governor says he is above both Pakeha and Maori – that he alone is Chief. Now, when Satan said, I am the greatest, Christ trampled him under foot. So the Queen says, that she will be chief for all men. Therefore, I say, let her be the protector of all the people.”

Others were even more strident, well and truly nailing their futures to the Pakeha ways, not the ancient Maori customs:

Te Ngahuruhuru (Ngatiwhakaue):

“The deceits do not belong to the Pakehas, but to the Maories alone. The Maori is wronging the Pakeha. I am an advocate for peace. Shew kindness to the Pakeha. Shew good feeling to this Governor. Look here, Maories! My word will not alter. I belong to the mana of the Queen, to the mana of the Governor. As to the setting up o a King – not that. Do not split up, and form a party for the Queen, and another for the Maori King: that would be wrong.”

It is this July 1860 runanga, or tribal council, that provides vital clues about how both Crown and Maori saw their relationship post Waitangi. As a tribal council where chiefs were required to vote in favour or against, and where – like Parliament today – a Hansard was taken of each speech and given to the speaker to double check its accuracy before being published, it was also an important and binding ratification of the terms of the Treaty which were now clearly expressed, both in English and in Maori.

If there was any ambiguity arising out of the 1840 Treaty regarding the cession of sovereignty, there was no ambiguity this time, and any honest debate of the “treaty principles” cannot take place without consideration of the 1860 speeches.

For the Waitangi Tribunal to lie to all New Zealanders about the sovereignty issue is a disgrace, and one that risks putting members of the Tribunal first up against the wall when the revolution comes, as it will if they continue down this divisive pathway.

If anyone wants an honest appraisal of the truth about Waitangi, in the actual words of the chiefs themselves, read The Great Divide.

EXTRA ADDED

Amazing, really, how a word that once simply meant “property procured by spear” is now an esoteric mystical word worthy of a Hindu guru and meaning whatever its 21st century translators want it to mean.

The problem for ordinary New Zealanders, Maori or Pakeha, is that the Waitangi Tribunal has official dibs on interpreting the Treaty, regardless of what ancient dictionaries or documents tell us the words really meant.

Did the Maori expect every last inch of their lives to be controlled by British law? Probably not. Nor did Britain expect to intervene in their customary habits except to the extent alluded to by Lord Normanby in his instructions to Hobson: “Until they can be brought within the pale of civilised life, and trained to the adoption of its habits, they must be carefully defended in the observance of their own customs, so far as these are compatible with the universal maxims of humanity and morals.” That paragraph, right there, is tino rangatiratanga in action – the governance of daily life retained by Maori until such time as they seek further access to British laws, and subject to exception for matters like cannibalism and human sacrifice.

It is submitted that no one in 1840 was really in the dark about what the Treaty meant. Overall sovereignty would transfer to Britain, day to day life would continue as normal for most Maori. Where there was intertribal conflict, or major crimes, British justice would intercede and adjudicate to the extent they were able. For routine matters, the rangatira – the ‘mayors’ – would sort it out within the hapu.

In practical terms, with no army and next to no police force, the British colonial administration was pretty much powerless for its first few years, so Maori justice continued to exist by default, tempered by missionaries and the appointment of native assessors, or magistrates.

To be fair, there was confusion within colonial ranks. In 1842 after Hobson’s death, upon reports of a tribe – who had not signed the Treaty – killing and eating members of a tribe who had – the Acting Governor Willoughby Shortland decided to impose the long arm of the law on the culprits. Chief Justice William Martin, Bishop Selwyn and Attorney-General Swainson tried to dissuade Shortland from his mission, primarily on the grounds of biting off more than they could chew, and secondly upon the novel legal argument that tribes who had not signed the Treaty were outside its jurisdiction. Historian and politician William Pember-Reeves would later describe this as “an opinion so palpably and daringly wrong that some have thought it a desperate device to save the country.” Certainly, the Colonial Office in London gave the New Zealand administration a swift kicking when it heard about it, “Her Majesty’s rule, said Lord Stanley, having once been proclaimed over all New Zealand, it did not lie with one of her officers to impugn the validity of her government.”200

Since 1972, however, the Treaty of Waitangi has taken on a modern spin of its own that appears to bear no resemblance to the way the Maori who signed it saw it.

Lawyer and passionate treaty activist Annette Sykes summed up the views of many within Maoridom today when she wrote: “The … tribes have reached a crossroads in their journey to protect their sovereignty and self-determination. In recent decades these highly articulate tribal nations have been leaders in a number of political, legal and economic strategies that promote the recognition of individual tribal entities as sovereigns enjoying government-to government relationships with the New Zealand Government. Their cries for self government having being made in forums from the Waitangi Tribunal through to the United Nations, and from the hallowed halls of political power in Wellington through to rank and file protests on the street.”201

Yet here is what the 200 chiefs assembled at Kohimarama in 1860 were told by the Governor:

“In return for these advantages the Chiefs who signed the Treaty of Waitangi ceded for themselves and their people to Her Majesty the Queen of England absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of Sovereignty which they collectively or individually possessed or might be supposed to exercise or possess.206

This is a key passage, so please note the Maori translation read to the chiefs in 1860:

“…tino tukua rawatia atu ana e ratou ki Te Kuini o Ingarani nga tikanga me nga mana Kawanatanga katoa i a ratou katoa, i tenei i tenei ranei o ratou, me nga pera katoa e meinga kei a ratou”. The word “tukua” means “cede” or “surrender” and “nga tikanga” the laws and lore, and “mana Kawanatanga katoa” means all sovereign authority.

Governor Gore Browne went on to read every clause of the English version of the Treaty, translated into Maori, into the record at Kohimarama for the chiefs to vote and comment on.

If you were looking for clarification on what the Treaty of Waitangi meant at the time, you’ve found it. Every main concept in the English version of the Treaty was re-stated in Maori, before a congress of Maori leaders – the biggest gathering of Maori leaders ever held to that point.

If there was ever a time to shout out “liar!”, this was it. If there was ever a time for Maori to say, “that’s not what we agreed to!”, this was it.

So what did the paramount chiefs say?

Sixty percent of those attending spoke in absolute explicit agreement with the way the Governor had described the Treaty and what it meant, and pledged their allegiance to Governor and Queen. A further 17% expressed similar sentiments, without making an outright declaration about it. Twenty one percent didn’t state an opinion on the matter, but talked of other things. Two percent appeared to be leaning against the Governor.

The tribes, as they would say on Survivor, had spoken, and in doing so had ratified the Treaty of Waitangi as most people understand it:

Eruera Kahawai (Ngatiwakaue, Rotorua): “Listen, ye people! There is no one to find fault with the Governor’s words. His words are altogether good.”

Menehira Rakau, (Ngatihe, Maungatapu): “Let us inquire into the character of the Governor’s address. I did not hear one wrong thing in the speech of the Governor.”

Rirituku Te Perehu, (Ngatipikiao, Rotoiti and Maketu): “The Governor’s address is right.”

Henare Pukuatua, (Ngatiwakaue, Rotorua): “Listen my friends, the people of this runanga. I have no thought for Maori customs. All I think about now is what is good for me. I have been examining the Governor’s address. I have not been able to find one wrong word in all these sayings of the Governor, or rather of the Queen. I have looked in vain for anything to find fault with. Therefore I now say, O Governor, your words are full of light. I shall be a child to the Queen. Christ shall be the Saviour of my soul, and my temporal guide shall be the Governor or the Law. Now, listen all of you. I shall follow the Governor’s advice. This shall be my path forever and ever.”

Tamihana Rauparaha, (Ngati Toa, Porirua): “The words we have heard this day are good.”

Karaitiana Tuikau, (Ngati Te Matera, Hauraki): “The Governor’s words are good.”

“The words of the Governor are good. Let the Queen be above all,” exclaimed Tohi, a Ngatiwhakaue chief.

The list could stretch on and on. Suffice to say not one chief accused the Crown of lying when it said it had taken absolute sovereignty over New Zealand when the Treaty was signed.

Constitutionally, their speeches and votes at the Kohimarama runanga amount to a full ratification of the English version of the Treaty, and it seems clear from the quotes above and on the preceding pages that the chiefs fully understood the concept of sovereignty.

However, this is also the reason the Littlewood Treaty document becomes irrelevant – it was superseded by Kohimarama.

For those who take issue, for example, with the “forests and fisheries” aspect of the Treaty, on the grounds that the words don’t appear in the Maori version, here’s the bad news: Governor Gore Browne read them into the record at Kohimarama, as you can see in his clauses listed earlier. This issue of attention to historical detail applies to goose and gander alike. The conference ratified sovereignty, but it also ratified forests and fisheries.

So let’s pause for a moment and return to contemporary scholarship.

In 1990, Professor Ranginui Walker wrote that rangatiratanga meant sovereignty and kawanatanga was merely a limited form of governorship:

“The chiefs are likely to have understood the second clause of the Treaty as a confirmation of their own sovereign rights in return for a limited concession of power in kawanatanga.

“The Treaty of Waitangi they signed confirmed their own sovereignty while ceding the right to establish a governor in New Zealand to the Crown. A governor is in effect a satrap…a holder of a provincial governorship; he was a subordinate ruler, or a colonial governor. In New Zealand’s case he governed at the behest of the chiefs…in effect the chiefs were his sovereigns.”

In this respect, Walker follows treaty historian Claudia Orange who says rangatiratanga would be a “better approximation to sovereignty than kawanatanga.”207

And yet, you’ve seen what Maori – and some of the Kohimarama attendees had actually signed the Treaty personally – understood the Treaty to mean, and sovereignty to mean. Can the academic claims about the Treaty actually be reconciled with historical fact?

It’s an important question. The meaning of the Treaty of Waitangi as it is currently pitched dominates public policy in this country, and it dominates the school curriculum. Our children are learning the academic version of the Treaty. There are many jobs you cannot be appointed to in the public sector unless you can demonstrate an acquaintance and allegiance to the modern interpretations of the Treaty.

None of this is written to belittle the wrongs that were done to Maori in breach of the Treaty. That’s not what this is about. Those grievances in many cases are real and require settlement. But if we are going to be honest about our past, it cuts both ways. We cannot move forward unless we have a clear understanding of the foundations. If our opinions and beliefs about the Treaty in the 21st century are based on a misunderstanding about what 1840 Maori thought, then our opinions and beliefs are founded on a lie. What actually matters is what Maori at the time really did think they were signing. The only way to find that out is to listen to their voices, rather than engage in endless debates about the meaning of the words as we currently understand them.

Anyone who wants to argue that Maori never ceded sovereignty can only do so by ignoring the Kohimarama runanga transcripts.

For twenty or so years after Waitangi, tribal Maori pretty much had continued to enforce their own laws and customs, because the British colonial apparatus of state in New Zealand was weak and spread too thinly to administer British justice against Maori by force. It was either voluntary compliance, or it was nothing.

What we see at Kohimarama, constitutionally, however, is an evolution of consent. After 20 years of partial integration, the chiefs not only ratified Waitangi in full but expressly called for a complete adoption of Pakeha tikanga.

Let’s hear the chiefs on how they perceived sovereignty operating. Was the Governor a ruler in name only, or one with the power to enforce the law, even to hold these same chiefs to account:

Hemi Metene Te Awaitaia: “I shall make the Governor’s address the subject of my speech. I shall speak first of the 4th clause, namely, – ‘In return for these advantages the chiefs who signed the Treaty of Waitangi ceded for themselves and their people to Her Majesty the Queen of England, absolutely and Without reservation, all the rights and powers of sovereignty which they collectively or individually possessed or might be supposed to exercise or possess.’ That was the union of races at Waitangi. I was there at the time, and I listened to the love Of the Queen. I then heard about the advantages of the treaty.

“In my opinion the greatest blessings are Christianity and the Laws. While God spares my life I will give these my first concern. When I commit a wrong, then let me be brought before the Magistrate and punished according to law. [emphasis added] Those are the good things.”

Winiata Pekamu Tohiteururangi: “The only thought that has occurred to me, is this – in former times I had but one lord (ariki), and now I shall have but one lord – only one. I shall have but one rule – not two. [emphasis added]”

[i] Letter, Marsden to Jowett, 11 August 1837,

see http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-McN01Hist-t1-b10-d79.html

[ii] The 1844 Maori Language Dictionary by William Williams translates ‘maru’ primarily as power, and gave the example, “Na te maru i a ia koia matou i matuku ai,” meaning, “In consequence of his power we were afraid”.

[iii] In Maori: “Whakarongo mai e nga rangatira Pakeha. Na koutou i tu mai ai ahau inaianei. Ko koutou anake te rangatira. Kia ki atu au kahore kau he rangatira o tenei motu, kahore rawa, kahore rawa. Na te Pakeha ahau i huhuti mai i te paru, nana ahau i horoi. Ko taku kupu tenei, kia kotahi te Ture mo te motu katoa.”

[iv] In Maori, the words were expressed: “Ko te Atua te tuatahi, ko te Kuini te tuatua, ko te Kawana te tuatoru. Kia kotahi te Kuini mo tatou. Whakamaramatia mai nga ture katoa kia noho ai tatou i roto i te ture kotahi.”